The Ambitious Life of Pawns

In the great treasury of chess metaphors there is none so pervasive as that of the insignificant pawn. It's also completely wrong.Reuben Fine once quipped that he'd rather have a pawn than a finger, but for over two and a half centuries chess players have known that pawns are no metaphorical pawns, at least since François-André Danican Philidor made his grandiose proclamation in Analyse du jeu des Échecs in 1749:

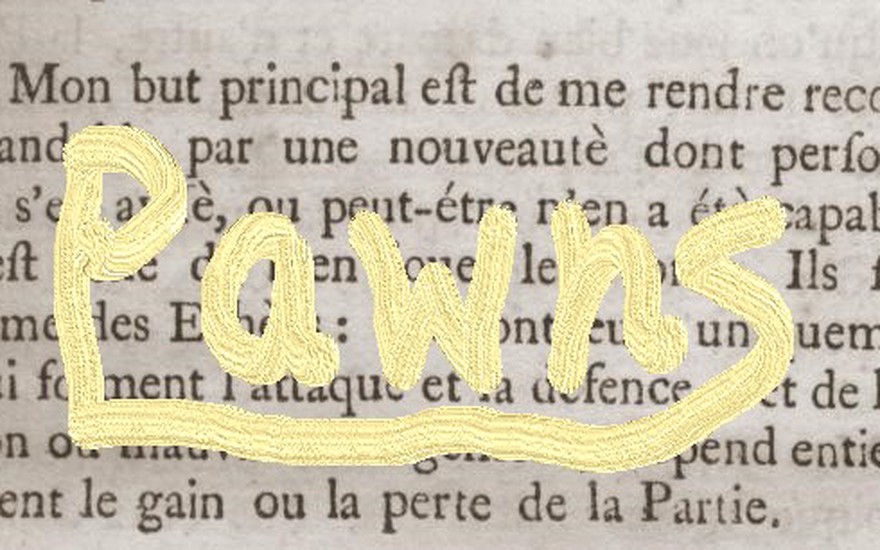

Mon but principal est de me rendre recommandable par une nouveauté dont personne ne s'est avisé, ou peut-être n'a été capable; c'est celle de bien jouer les pions; ils sont l'âme des Echecs: ce sont eux-mêmes qui forment uniquement l'attaque et la défense et de leur bon ou mauvais arrangement dépend entièrement le gain ou la perte de la partie.

My main purpose is to gain recognition for myself by means of a new idea of which no one has conceived, or perhaps has been unable to practice; that is, good play of the pawns; they are the soul of chess: it is they alone that determine the attack and the defense, and the winning or losing of the game depends entirely on their good or bad arrangement.

Pawns make up half of all the pieces on the board after all and each of them possesses the latent power of a queen. The whole tenor of battle changes if we play d4 instead of e4 and we commonly define ourselves as chess players in that way. It is the pawns which grab space and seize control of the center at the outset and their formations determine everything: our plans revolve around utilizing outposts and open files and attacking weakness in the pawn structure. Pawns can clear the field and unleash the bishops or they can clog things up and empower the knights.

Sometimes they sacrifice themselves to clear or block a path or shatter a formation. A lone pawn can attack and completely embarrass two rooks at once, and with the help of just one partner they can race down the board like Sam and Frodo into Mordor and end the game to the complete surprise of a distracted opponent. It frequently happens that knights and bishops are given up to stop a single advanced pawn, and sometimes even a rook or queen.

I became fascinated with pawns while reading Pawn Power by Angus Dunnington. I've never heard anyone recommend it, but it's a great primer because it has a lot of prose, which I think is really important for understanding chess, and it's only about 100 pages long, so you can actually finish it in a reasonable time. Immediately after finishing that I sought out Secrets of Pawn Endings by Karsten Müller and Frank Lamprecht because Jacob Aagaard had praised it somewhere. It is probably the most important and enjoyable chess book that I've ever read. Although I thought I was studying pawn endgames, I came away from that experience with a much deeper understanding of middlegame structures and even opening moves—a better understanding for the soul of chess.

The joy of reading that book, however, had nothing to do with the deeper understanding which I appreciated only later. It had to do with the number of crucial positions in which the solution was an almost incomprehensible pawn move. The board could be open with just a few pieces and the difference between a win and a loss might be a pawn move threatening nothing immediate, but which many moves later would block the enemy king from catching a passed pawn or would shift the key squares for defense just enough to hold a draw. Sometimes the explanation would dawn on me like a flush of golden sunshine, while other times I couldn't make sense of it at all—and yet even then the problem itself seemed beautiful somehow.

We're always talking about computer moves and human moves these days, but of course everyone is capable of seeing all the legal moves on the board. When we call a move "inhuman" we mean that it doesn't seem to satisfy our explanatory principles of chess or that it solves a problem we haven't appreciated yet. What seems inhuman to me might be natural for grandmasters and what seems inhuman to grandmasters of today might become second nature for the new generation who use computers like coaches and reverse-engineer engine moves to understand the game more deeply. Many of these so-called "computer moves" are pawn moves, and it's no coincidence that many of the most awesome and beautiful chess studies are endgame studies involving pawns.

I recently spent time looking through some tactics in pawn endings and put them together in an interactive study which you can use to test yourself. Mark Dvoretsky wrote that "the study of pawn endings chiefly boils down, not to the memorization of exact positions, but to the assimilation of standard techniques." I think trying to solve these examples will help you assimilate standard techniques, but honestly the plan is just to have fun with pawns. I've tried to use positions with very forcing sequences, but I've included some guidance when something interesting could be solved in different ways.

I've been rereading War and Peace this winter in which Tolstoy spends a lot of pages discussing history and historiography. He argues that written history is always incomplete, and the "great man" approach is especially problematic, because complex endeavors like wars and even battles unfold as millions of little decisions made by the participants. It can be difficult to know why a battle turned out in a certain way. It might be the general's plan or the executive work of the officers, but it might be because one soldier panicked at the sight of a dying horse, that fear spread through the ranks, and a crucial part of the battlefield collapsed, which is the type of thing historians can never know. It could be all of those things and others besides.

Of course in chess we can reconstruct each discrete move in perfect detail, but I think his point about the importance of the metaphorical pawns in the grand sweep of history is interesting. I'm sure that the popular metaphor of the pawn as a dispensable minion will always be around, but for chess players who know better it's interesting to reflect that Philidor's insight was by coincidence published in the golden age of enlightenment thinking, when the rights of "commoners" were being expanded and codified, and Europe and America were heading toward political and social revolutions to redress in fits and starts and half-measures the position of their ambitious pawns.